It was a surreal scene for a teenage girl to be cruising down the highway in 1956 wedged in the front seat of a Pontiac Star Chief between her father and Elvis Presley. But that was the dizzying case for 18-year-old Wanda Jackson right at the time when rock and roll was percolating and beginning to flip American teen culture upside down.

It was a surreal scene for a teenage girl to be cruising down the highway in 1956 wedged in the front seat of a Pontiac Star Chief between her father and Elvis Presley. But that was the dizzying case for 18-year-old Wanda Jackson right at the time when rock and roll was percolating and beginning to flip American teen culture upside down.

As a budding country music starlet from Oklahoma City, Jackson was recruited as the lone female performer to play alongside rock and roll pioneers such as Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, and Elvis. “They were kind of like my brothers,” Jackson told Good News. “I always kind of preferred the company of men, anyway. I had my dad there and it made it possible to work with that many men. I wouldn’t have done it had I been alone. I couldn’t have.”

With her father as her chaperone and the watchful guardian of her reputation, she was not permitted to ride with the guys, but Elvis was allowed in the front seat of their Pontiac on the way to the next concert stop.

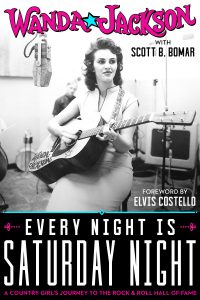

Jackson, 80, known as the Queen of Rockabilly, still performs live, has released dozens of albums, and has been nominated for multiple Grammy awards. Her many fans include Bob Dylan, Adele, Jack White, Cyndi Lauper, Bruce Springsteen, and Elvis Costello. Jackson’s new autobiography Every Night Is Saturday Night: A Country Girl’s Journey to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (BMG) is a coming-of-age memoir of how a knock-out performer could have a five-decade career in country, rock, and gospel and not lose her soul.

Without a doubt, Jackson’s relationship with Elvis played a key role in the trajectory of her career. When they first met in 1955 at a radio station on the first stop of a tour, she had never heard of him. Nevertheless, Jackson thought he was handsome and charming. Not long after, they began dating. “He asked me to be his girl, and I had his ring,” she said. She wore it around her neck for about a year before their career paths tamped out their long-distance relationship. The romance did not last, but she still has his ring – and fond memories.

Originally, Wanda’s father couldn’t comprehend Elvis. “I ain’t never seen nothin’ like that,” he told Wanda as they both watched Elvis with a bright yellow coat and slicked-back pompadour getting into the front seat of his bright pink Cadillac. “Elvis might as well have been getting into a rocket ship,” Jackson recalls in her book. “You might should stay away from that one, Wanda,” her dad said. “I think this Elvis character could be a nut.”

Originally, Wanda’s father couldn’t comprehend Elvis. “I ain’t never seen nothin’ like that,” he told Wanda as they both watched Elvis with a bright yellow coat and slicked-back pompadour getting into the front seat of his bright pink Cadillac. “Elvis might as well have been getting into a rocket ship,” Jackson recalls in her book. “You might should stay away from that one, Wanda,” her dad said. “I think this Elvis character could be a nut.”

Eventually her father grew to admire Presley. It was the young singer from Memphis that convinced Jackson to transition from country music to the newly minted rock and roll sound that was becoming a cultural sensation. “We knew that Elvis had stirred things up and times were changing,” Jackson told me. Presley tried to convince the Jacksons to look to the youth market – the ones buying the records and calling the radio stations.

Wanda’s father saw the wisdom in the advice. “I think Elvis is right,” he told his daughter. “I think there’s a new trend coming.” Everything was happening so quickly. “We didn’t know how long it would last but Elvis made me promise that I would try it,” she said. Despite her misgivings, she eventually knocked out spitfire hits such as “Mean, Mean Man,” “Fujiyama Mama,” “Hot Dog! That Made Him Mad,” and “Let’s Have A Party.”

Jackson was a certifiable shimmering star and glamorous renegade in the male-dominated golden era of rock. She played guitar, got scolded at the Grand Ole Opry for trying to get on stage with exposed shoulders, and provocatively had an African-American piano player at a time when strict segregation was brutally enforced. Her 2009 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction finally celebrated her indisputable musical legacy.

At the same time, Wanda and her husband, Wendell – an IBM computer programmer who became her manager and publicist (who died last year) – were suffering all the side effects of fame, partying, and life on the road. “After about 10 years it was pretty hard,” Jackson said. “Wendell was very jealous and that caused problems. … There was a lot of drinking – the outcome of that was treacherous. … We loved each other. We didn’t ever think about divorce. Murder, a couple of times,” she joked with laughter. “No, we loved each other, but we were drinking too much. We were gone too much. We were arguing. I couldn’t live that way and neither could he.”

The success, liquor, and showbiz lights were not enough distractions to heal her spiritual ache. “Sometimes I would lie in bed at night with a gnawing feeling in the pit of my stomach that something was missing,” she wrote. “I felt restless and anxious. … But I still couldn’t shake that dull but persistent sense of emptiness inside.”

In 1971, The Living Bible, paraphrased in common language, was published and she read it out loud to Wendell as they were on the road. “We tried to make sense of it,” she said. “We were really searching.” While they were away, the Jackson’s two children were being cared for by Wanda’s mother. The kids loved the new pastor at their church and hounded their parents to hear him preach. “Even though we were open to trying to understand the Bible during those long stretches of interstate, we weren’t that anxious to go hang out with a bunch of church people,” Jackson wrote. “That wasn’t really our crowd.”

Between tours, the pastor informally connected with the Jacksons and ended up being as personable and engaging as their children had reported. What Wanda and Wendell remembered from their time with the minister was his direct message: “Everyone needs Christ, no matter who you are. Sometimes people are afraid to admit they need Christ, and they’re afraid to turn to Him because they feel like they’re not good enough or they’ve done some things that make them feel like God couldn’t possibly love them. But He does.”

They wrestled with the weight of those words while they were back on tour. “We were running,” she recalls. “Running from the reality that our marriage was suffering. Running from the fear that our lives were unraveling. Running from Brother Paul’s words that everyone needs God.”

When they returned home from the concerts, they fulfilled the promise to their kids that they would attend church. “We got up late – kinda hung over – but we were late getting to church,” she said. While in the service, Wanda sensed a divine voice say, “Walk with me.” She turned to Wendell. “There is something I’ve got to do,” she said. “Let me out of this pew. I’ve got to get right with the Lord.” He joined her.

“We took hands and walked down the aisle and gave our hearts and lives to Christ,” she recalled, as the congregation sang the old hymn, “Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior.” “It was just unbelievable. The pressure was lifted off. The guilt, the sin, was lifted off. It was just marvelous. We were two new creations in Christ. Everything changed for the better.”

The shift of spiritual dynamics also detoured Jackson’s career path. “I started to record gospel. That’s where my heart was,” she told me. “I wanted everyone in the world to know the salvation that I experienced.” That decision was fraught with its own challenges. “I had never had stage fright playing in honky tonks, but the first few times I sang at churches, I was so scared I was throwing up before I went on,” she wrote. “I was used to singing for people who were there for a party. It was nighttime, and there was smoke, and everyone was drinking and acting silly and having fun. Suddenly, there I was in a long dress – not a miniskirt – and no fringe and no go-go boots. And it was daylight and everyone was sober! I didn’t know how the church folks would react to me.”

She was caught in a cultural and spiritual skirmish. The country music disc jockeys wouldn’t play her gospel. “They thought it was too churchy,” she said. “And the church, on the other hand, thought I was still too country. I fell through the cracks.” Over the next decade, she recorded half a dozen gospel albums and she and Wendell shared their gospel message all over the world.

Jackson’s career took on another unexpected twist with the eruption of a rockabilly revival in the 1980s. She discovered that she was still considered a star in Europe and Scandinavia. The fans lined up to hear Jackson playing her classic hits. Meanwhile, The Stray Cats, The Blasters, X, The Cramps, and Rosie Flores were spearheading a rockabilly resurgence in the United States. Her songs had once again found a receptive audience.

“She’s vibrant and edgy without being abrasive, and sweet without being saccharine,” observed musician Roseanne Cash, daughter of Johnny Cash, at her Rock Hall induction. “This is a woman who has rhythm and joy, in equal parts, to the depth of her soul…. She’s not a red-carpet-celebrity-hand-out-rehab-tabloid kind of person. She’s a person of strong religious conviction, deep integrity, a road warrior, and a rock and roll queen.”

Each generation has turned in one way or another back to Wanda Jackson’s music. Her last two albums were produced by critically-acclaimed recording gurus Jack White and Justin Townes Earle. “I believe God has given me two deep desires, and He’s provided me with the opportunity to fuel them both,” she testifies in her book. “First, I love to rock ‘n’ roll. It’s great to get on the stage, feel those drums pounding behind me, and get the audience on their feet. Second, He gave me the desire – and also the courage – to talk about my faith onstage, whether I’m at a church revival or a punk rock club.”

She testifies that there is a “holy hush” that falls on the audience when she talks about her faith in God. “Every once in a while, I’ll have a drunk girl sarcastically yell out ‘hallelujah’ or something. Some guys have mouthed off a little bit, but the audience will shush them for me, so I don’t have to say anything,” she wrote. “I think my fans respect me, but I also try to be cool and respect them by not talking too long.”

After her talk, Jackson launches into Hank Williams’ “I Saw the Light.” “Almost everyone knows the words,” she said. “They start clapping and singing along with me. It’s like a Baptist revival.”

Hank deftly crosses over in honky-tonks and sanctuaries. So does Wanda.

“I’ve learned what it means to find peace and meaning, sometimes in the face of adversity,” she concludes. “I’ve learned to find my grounding in a good man, a good family, and most importantly, in a good God, who is the source of all light and truth. These are the influences that have allowed me to keep the musical party going for decades.”