“Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world” (James 1:27). United Methodists of all political stripes should be able to agree on ministry to and with widows and orphans.

“Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world” (James 1:27). United Methodists of all political stripes should be able to agree on ministry to and with widows and orphans.

At least that is the hope of the Rev. Wayne Lavender, a United Methodist pastor who is making a run/walk/drive trek from the east coast of the United States to the 2016 General Conference of the United Methodist Church in Portland, Oregon.

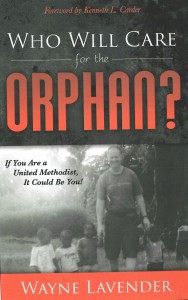

Lavender is the author of Who Will Care for the Orphan: If You Are A United Methodist, It Could Be You and executive director of Foundation 4 Orphans. His cross-country awareness campaign is focused on embracing the world’s estimated 210 million orphans as a missional priority of the UM Church. His petition to the General Conference has been assigned to the General Administration committee.

“Today the denomination, within the United States, is in great decline,” writes Lavender. “We are deeply divided over theological and political issues and have seemingly lost our way. We do not have a single missional priority through which we can focus our missional activities and ignite our evangelical efforts.” He believes that ministry to orphans could be a unifying issue that the entire denomination can support.

Lavender reminds United Methodists that there are 30 specific times the Bible “calls for its followers to care for orphans.” At the same time, he points to UNICEF statistics that claim 26,000 children die daily from the effects of extreme poverty, an annual total of 10 million children.

“The crisis of orphans and vulnerable children is one of the most pressing ethical issues of our day, and yet it remains predominately the silent concern with little attention, publicity, funding or policies,” writes Lavender.

Lavender is able to make his appeal not only from the Bible, but also from our shared Methodist roots. “John Wesley’s missional focus was on improving the human condition of the poor, including orphans and widows,” he observes.

Shortly after his experience at Aldersgate in 1738 where his heart was “strangely warmed,” Wesley witnessed the remarkable ministry of an orphan home in Germany. He was greatly impressed and referred to it in his journal as “that amazing proof that ‘all things are still possible to him that believeth’” (Journal, June 24, 1738).

According to Lavender, Wesley established orphan homes in Great Britain. He also supported George Whitefield’s life decision to care for orphans in the American Colonies, and wrote to him in 1770 with these words: “Can anything on earth be a greater charity, than to bring up orphans?”

Most United Methodists are aware that John Wesley embraced the unconventional practice of field preaching when he began proclaiming the gospel outside the confines of a pulpit. “At four in the afternoon I submitted to be more vile, and proclaimed in the highways the glad tidings of salvation…” he famously wrote in 1739.

Wesley’s decision was in direct response to witnessing his friend George Whitefield preach outdoors in 1738 so that he could raise funds for a new orphanage in Savannah, Georgia. “Had Whitefield not chosen to raise funds for an orphanage,” writes Lavender, “he might not have made the decision to preach outdoors depriving Wesley of this model.”

“Embracing of orphans and vulnerable children as the missional priority of the denomination will bring disparate components of the UM Church together to address a Biblically based, Wesleyan-supported common cause. We can mitigate the daily death toll and simultaneously find a raison d’ê·tre.”