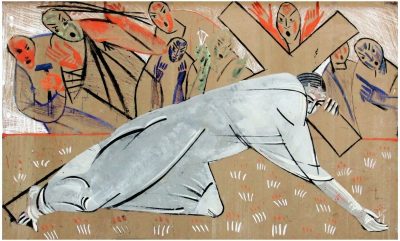

Artwork: “Station of the Cross: Fall” by Ostap Lozynsky of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com.

By Steve Beard

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

“On a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,” we sang. “The emblem of suffering and shame / And I love that old cross where the Dearest and Best / For a world of lost sinners was slain.”

Modern day hipsters may roll their eyes at the sentimental lyrics, but they stuck with me. It was a sing-a-long song about the most brutal injustice in human history and it became a well-known gospel chorus for an entire generation. Johnny Cash recorded four different versions. It was also recorded by Al Green, Ella Fitzgerald, Merle Haggard, Mahalia Jackson, Patsy Cline, Willie Nelson, and Loretta Lynn.

“The Old Rugged Cross” was written in 1913 by a Methodist preacher named George Bennard (1873-1958) who was converted to faith as a young man after walking five miles to a Salvation Army meeting. At age 15, he had lost his father in a mining accident. Bennard found new life and inspiration in giving his heart to a Savior riddled with nail scars who had conquered death.

“The crucifixion is the touchstone of Christian authenticity, the unique feature by which everything else, including the resurrection, is given its true significance,” writes the Rev. Fleming Rutledge in her magisterial book, The Crucifixion. “Without the cross at the center of the Christian proclamation, the Jesus story can be treated as just another story about a charismatic spiritual figure. It is the crucifixion that marks out Christianity as something definitively different in the history of religion. It is in the crucifixion that the nature of God is truly revealed. Since the resurrection is God’s mighty trans-historical “Yes” to the historically crucified Son, we can assert that the crucifixion is the most important historical event that has ever happened.”

When my father would serve communion at our United Methodist church, he said: “The body of Christ, broken for you. Feed on him in your heart by faith with thanksgiving.” Those words can still bring tears to my eyes. Sundays come and Sundays go, but those words stick in my soul. The Lamb of God was betrayed by a sleazy friend, ambushed by a well-armed battalion, falsely accused by conniving religious leaders, condemned by a spineless politician, and publicly executed before his weeping mother as cries of ridicule filled the air and birds of prey circled overhead.

To the abused who feels shame, this Crucified Christ stands with empathy. To the wrongly accused, this Crucified Christ stands with the truth. To all those victimized by injustice, thisCrucified Christ stands with the innocent. “Come to me, all you who are weary … and I will give you rest,” Jesus said.

There are countless examples of contemporary Christian leaders who fail to live up to the Jesus ideal. Unfortunately, that has been the failed track record of Church history. But the Christ who was humiliated and shivved in the side on Golgotha is the genuine article. I try to keep my eyes on him. In every conceivable way, Jesus is counterintuitive. Who would have ever come up with a game plan of forgiving your enemies, turning the other cheek, and loving those who plot your demise?

“Even the excruciating pain could not silence his repeated entreaties: ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’ The soldiers gambled for his clothes,” wrote the late Anglican scholar, the Rev. Dr. John R.W. Stott. “Meanwhile, the rulers sneered at him, shouting: ‘He saved others, but he can’t save himself!’ Their words, spoken as an insult, were the literal truth. He could not save himself and others simultaneously. He chose to sacrifice himself in order to save the world.”

I understand the reluctance to spend inordinate time dwelling on the sufferings of Christ. It’s macabre and grotesque. It is the stigma of the story, the stain, the moment you turn your head away. But it is an inescapable part of redemption’s drama.

For those in the modern era, it is hard to imagine a time when crosses weren’t sold as bedazzled necklaces, home décor accessories, or garish t-shirt designs (“Body Piercing Saved My Life”). The cross was not always viewed as an icon for a faith dedicated to a kingdom that was not of this world.

“To the early Christians it was a symbol of disgrace. They could not look upon it as an object of reverence,” wrote historian George Willard Benson. “Death by crucifixion was the most shameful and ignominious that could be devised. That Christ should have been put to death, as were debased and despised criminals, was bitterly humiliating to his followers.”

Over the centuries since Christ’s blood-soaked public execution, the cross was slowly transformed from a symbol of shame and humiliation to one of victory and triumph for all of us who have been shamed and humiliated.

In his critically acclaimed book, Dominion: How The Christian Revolution Remade the World, British scholar Tom Holland points out that the tales of a human-divine hybrid were not unfamiliar in ancient history. Mythology from Egypt and Greece and Rome featured heroic monster-slayers and a pantheon of warlords that claimed to be empowered from the heavens.

“Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings,” writes Holland. “Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque.”

The gospel is upside-down storytelling. Perhaps it helps explain the inexplicable allure of Jesus. The story does not end on a towering cross on the edge of town where the dying moan and mothers weep. More was to unfold.

Osiris, Zeus, and Odin are worshipped no longer. The Savior of the widow and orphan and tax collector is still worshipped around the globe. That is not chest-puffing triumphalism; it is simple reality.

“The crucifixion of Jesus, to all those many millions who worship him as the Son of the Lord God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was not merely an event in history, but the very pivot around which the cosmos turns,” writes Holland.

Holland only returned to the church of his childhood while writing his book. His thinking was dramatically affected while filming near a battlefront in an Iraqi town where Islamic State fighters had previously used crucifixion as a means of terror. “For the first time, I was facing the reality of crucifixion as it had been practiced by the Romans, face to face,” he told the Church Times. “It was physical in the air … people had been crucified by people who wanted the effect of crucifixions to be that which the Romans had wanted. They wanted to generate the sense of dread and terror and intimidation deep in the gut, and I felt that….

“I realized how important it was to me to believe that, in some way, someone being tortured on the cross illustrated the truth of the possibility that power might be vanquished by powerlessness, and that the weak might vanquish the strong, and that … hope might be found in the teeth of life in despair.”

Perhaps the hope found in the horror of the cross of Christ is the “assertion that the same God who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death,” wrote novelist Dorothy Sayer. Explain that to an unbeliever, and “they may not believe it; but at least they may realize that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. This article originally appeared in Good News in 2020. Artwork: “Station of the Cross: Fall” by Ostap Lozynsky of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com.