Dublin was still rubbing sleep from its eyes. It was the crack of dawn. Well, not literally – it just seemed that way. The sidewalks along historic statue-lined O’Connell Street were largely empty as I paced toward Trinity College on the south side of the Liffey River. In just hours, tourists would once again be shoulder to shoulder up and down the popular thoroughfare.

But for the moment, it was a crisp and peaceful morning. For a city known for its literary superstars such as James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, and Seamus Heaney, the most celebrated and valuable book in town is a Latin text created around 800 A.D. by a team of obscure monks on a tiny wind-whipped island 200 miles north of the Irish capital. This was my opportunity to see the mysterious and captivating book.

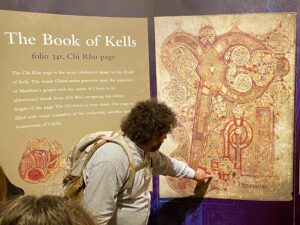

Believed to have been developed in a monastery on the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, the Book of Kells is a 1,200 year old “illuminated manuscript” of the Four Gospels of the New Testament. “You can imagine the monks inside their beehive-shaped stone huts, battered by sea winds with squawking gulls outside, bent over their painstaking work,” observed Martha Kearney, a British-Irish journalist, for the BBC.

Within historical context, Johannes Gutenberg would not create the printing press for another six centuries. The mere existence of the Book of Kells is remarkable.

Surviving an assortment of vicious Viking raids on Iona, the sacred text was moved to the monastery of Kells in County Meath, northwest of Dublin. The magnificent volume measures 13 x 10 inches and contains 340 folios (thus 680 pages) made of calfskin vellum. The collected manuscript – created by a team of scribes and artists – was eventually sent to Dublin for safe keeping at Trinity College in 1661.

There is kind of a bittersweet irony that the elegant scribes of the world-famous Book of Kells are known simply as Hand A, Hand B, Hand C, and Hand D. The artistic collaborators – probably three – produce portraits and scenes that are simply otherworldly. Some of the mind-boggling precision can only be fully appreciated with a magnifying glass.

Weeks prior, I had signed up with a private early morning lecture group to learn more about the treasured medieval book. It was also a crass move on my part to skip the legendarily lengthy lines to see the masterpiece. One couple in my group was from Hawaii, another from Texas, still yet another family was from Italy. We joined millions of previous tourists that have filed past the heavily-secured manuscript in order to be within close proximity of such an utterly unique combination of sacred text and enigmatic art.

More than a thousand years ago, it was described in The Annals of Ulster as the “chief relic of the western world.” It was also reported that it had been stolen from Kells in 1006 and later discovered – without its richly bejeweled cover – and possibly buried under ground.

Today, the same engineers who designed the protective cases for the Crown Jewels and the Mona Lisa were assigned to the Book of Kells. In his book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, Christopher de Hamel reports that the security surrounding the Book of Kells is “as complex as presidential protection undertaken by the secret services of a great nation.” In order for him to view the manuscript personally, he sat at a “circular green-topped table, prepared in advance with foam pads, a digital thermometer, and white gloves.”

He was granted truly privileged access. Nevertheless, to those without the white gloves, the luster of the treasure still shines through as a testimonial to faith, devotion, and imagination. The sacred and exotic art includes the first full-page portrait of the virgin Mary and Jesus in western manuscripts, intertwining snakes, eucharistic chalices, intricate knotwork, a stunning Chi-Rho (Greek monogram for the name of Christ), vivacious peacocks, tightly coiled spirals, knotted ribbons, Christ tempted by the devil, and a portrayal of the gospel evangelists as the “four living creatures” (a tetramorph): Matthew as the man, Mark as the lion, Luke as the ox, and John as the eagle.

The colorful palette includes black, red, lilac, pink, purple, and yellow ink.

The 12th century historian Gerald of Wales is assumed to have been describing the Book of Kells when he wrote: “Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it. Look more keenly at it and you will penetrate to the very shrine of art. You will make out intricacies – so delicate and subtle, so exact and compact, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid – that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man.”

Even modern day scholars have a hard time hiding their astonishment. “The writing, in huge insular majuscule script, is flawless in its regularity and utter control,” writes de Hamel, an expert on medieval manuscripts. “One can only marvel at the penmanship. It is calligraphic and as exact as printing, and yet it flows and shapes itself into the space available. It sometimes swells and seems to take breath at the ends of lines. The decoration is more extensive and more overwhelming than one could possibly imagine. Virtually every line is embellished with color or ornament.”

We will never know the names of these saints of quill and ink with a mindfulness for bewildering detail, righteous pizzazz, and fantastical beasts. The ancient Scripture teaches that we are “surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses.” In that number are the artists and scribes who painstakingly stretched their imaginations and devotion to create the Book of Kells. To those saints, with all gratitude, thank you.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.