Frederick Douglass grew up under the perverse shackles of slavery on a plantation in Maryland 200 years ago. He never knew the identity of his father, barely saw his mother, and witnessed unspeakable violence and bloodshed before he turned 10 years old. He was proselytized under a warped version of Christianity that had a Bible in one hand and a bullwhip in the other. It was piety unrecognizable to the Prince of Peace.

Frederick Douglass grew up under the perverse shackles of slavery on a plantation in Maryland 200 years ago. He never knew the identity of his father, barely saw his mother, and witnessed unspeakable violence and bloodshed before he turned 10 years old. He was proselytized under a warped version of Christianity that had a Bible in one hand and a bullwhip in the other. It was piety unrecognizable to the Prince of Peace.

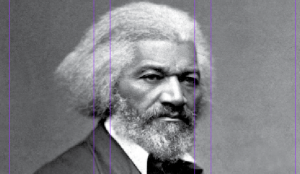

As one who escaped the bonds of slavery, Douglass (1818-1895) would become the most eloquent abolitionist orator and the most steadfast defender of liberty, equality, and justice. “Douglass spoke as a man born into bondage in America more than forty years after the Declaration of Independence had proclaimed that all men were equal and endowed by God with liberty,” historian D. H. Dilbeck reports in Frederick Douglass: American Prophet, a new spiritual autobiography.

At eight years old, Douglass was sent to live with a Methodist family in Baltimore. The wife, Sophia, was kind and devout and treated Frederick with the love that children deserve. Bible reading, hymn singing, and prayers were commonplace. One night, he heard Sophia reading the Old Testament story of Job aloud. The desolation of Job’s life was spelled out: death, poverty, and relentless calamity.

“Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord. In all this Job sinned not, nor charged God foolishly.”

“How could this be?” young Frederick asked himself. Why are the righteous stricken with destruction while the evil count their fortune? Where is God? Was this all part of a divine plan? When he should have been identifying with a Sunday school story such as young David slaying the belligerent bully Goliath, instead he connected with the stark horror story of a man whose entire family is decimated.

When asked about their captivity, some fellow slaves repeated the slaveholder’s propaganda that God made white people to be masters and black people to be slaves. Others told him that it was God’s predestined plan for the planet. Douglass rejected these false precepts. “It was not color, but crime, not God, but man, that afforded the true explanation of the existence of slavery,” Douglass concluded. Judging from the biblical messages of the prophets and the King of Kings, it was greed and spiteful hearts of humans that stole liberty and equality from those who were born free.

Wanting to learn more about Job, Frederick asked Sophia to teach him to read. He soon mastered the alphabet and began to spell. Sophia was overjoyed – until she announced the progress to her husband. Horrified, he demanded that the lessons end immediately. “Learning would spoil the best n***er in the world,” he said, because slaves who knew how to read – especially the Bible – became “disconsolate and unhappy.” One can only imagine the fear that would run through a slaveholder’s blood as those kept in chains read about Moses telling Pharaoh, “Let my people go!” Sophia promptly ended the lessons.

Douglass recalled her transformation as proof that “slavery can change a saint into a sinner, and an angel into a demon.” At the same time that young Fredrick’s heart was searching for a relationship with God, he witnessed firsthand the way that the prevailing slaveholding culture blinded the churchgoers to biblical justice and the gospel of love.

Hidden away at night, Frederick taught himself to read using old copies of Webster’s spelling book and Methodist hymnals. The saga of Job launched Douglass into mastering the language – the written words that held power to unchain the heart – that could literally help free men, women, and children. “Devout masters did all they could to keep the sacred truth of the Gospel from their slaves,” Dilbert wrote. “Yet the confounding experience of Job, who heard God in the whirlwind, proved far too compelling to a young boy who had wrestled with the problem of evil. Nothing could keep Frederick from the Bible and from learning to read.”

Remarkably, Douglass scoured the streets looking for passages of Scripture to piece together. “I have gathered scattered pages from this holy book, from the filthy street gutters of Baltimore, and washed and dried them, that in the moments of my leisure, I might get a word or two of wisdom from them,” he wrote.

Douglass would eventually write three best-selling autobiographies. “I was not more than thirteen years old, when I felt the need of God, as a father and protector,” he wrote in My Bondage and My Freedom. “My religious nature was awakened by the preaching of a white Methodist minister named Hanson. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God … and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God, through Christ.”

Douglass was also befriended by Charles Johnson, a black lay preacher, who told him to pray. “I was, for weeks, a poor, brokenhearted mourner, traveling through the darkness and misery of doubts and fears. I finally found that change of heart which comes by ‘casting all one’s care’ upon God, and by having faith in Jesus Christ, as the Redeemer, Friend, and Savior of those who diligently seek Him.”

Douglass testifies that seeking after God transformed his life. “After this, I saw the world in a new light. I seemed to live in a new world, surrounded by new objects, and to be animated by new hopes and desires,” he claimed. “I loved all mankind – slaveholders not excepted; though I abhorred slavery more than ever. My great concern was, now, to have the world converted.”

Douglass spent the rest of his life battling for the rights of those left out and forgotten: women, Native Americans, and immigrants. He preached and published with the intensity of an Old Testament prophet and the grace of a nail-scarred savior. He had a lifelong “lover’s quarrel” with the Christian church in America that defended or looked the other way while men, women, and children were sold on auction blocks. The complicit preachers armed with a false gospel “have shamelessly given the sanction of religion and the Bible to the whole slave system,” Douglass said.

The message and struggle of Old Testament prophets helped Douglass make sense of the prevailing worldview that devalued and degraded an entire race of people. He “aspired to speak to America as Isaiah and Christ once spoke,” observed Dilbeck, “with words of rebuke and warning, exhortation and encouragement, grace and liberty, hope and truth.” The voice of Christ and the prophets “provided a radical, contrarian vision of righteousness: to care for the marginalized, oppressed, widowed, and orphaned; to heal the brokenhearted; to set free the captives.”

Douglass’s faith was his anchor of hope throughout his life. Preaching in a Methodist church in Washington D.C. near the end of his life, Douglass confessed that when he faced despair about the future of his race and nation, he reminded himself, “God reigns in eternity, and that whatever delays, whatever disappointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty, and humanity will ultimately prevail.”