For more than 150 years, The Salvation Army has been the most consistent, creative, and trustworthy symbol for a warm-hearted faith and a generous helping hand for those in need. During this year’s treacherous hurricane season, it was a frontline responder – serving 1.3 million meals, offering prayers, and providing supplies to traumatized survivors in the Houston area, Florida, as well as those across the Caribbean, including Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

For more than 150 years, The Salvation Army has been the most consistent, creative, and trustworthy symbol for a warm-hearted faith and a generous helping hand for those in need. During this year’s treacherous hurricane season, it was a frontline responder – serving 1.3 million meals, offering prayers, and providing supplies to traumatized survivors in the Houston area, Florida, as well as those across the Caribbean, including Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

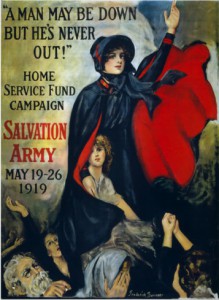

With a legacy of rushing into where the need is greatest, The Salvation Army has earned a coveted reputation for integrity and compassion without prejudice or discrimination. Having served survivors of every major national disaster since 1900, its industriousness is a powerful testimony for its purpose and passion. Last year, more than 3 million people received holiday assistance, more than 10 million nights of lodging were provided to those in need, and more than 56 million meals were served to those who were hungry. Nearly 30 million Americans receive assistance through it each year. It is simply indispensable.

The Salvation Army was launched in Victorian London by William and Catherine Booth, a powerhouse Christian couple who were overwhelmed and horrified by the conditions of the poorest of the poor – the “submerged tenth” – who had virtually no escape from the clutches of misery and poverty. Booth’s spirited response was, “Go for souls and go for the worst!”

He was passionate about reaching the people the established church had overlooked or ignored. “While women weep, as they do now, I’ll fight,” Booth proclaimed. “While little children go hungry, I’ll fight; while men go to prison, in and out, in and out, as they do now, I’ll fight — while there is a drunkard left, while there is a poor lost girl upon the streets, where there remains one dark soul without the light of God — I’ll fight! I’ll fight to the very end!”

Today, The Salvation Army – complete with its iconic uniforms and brass bands – operates in 129 nations of the world. Commissioner George Scott Railton and seven “Hallelujah Lassies,” as they were called in those days (Google teenager Eliza Shirley), arrived in New York in 1880. “Salvationists marched up the avenues and down the boulevards – even raiding brothels, saloons, and dance halls – in pursuit of lost souls. Their ‘Cathedral of the Open Air,’ a figurative canopy spread over the city, turned all of New York into sanctified ground,” writes Diane Winston in Red-Hot & Righteous: The Urban Religion of The Salvation Army (Harvard).

Winston reports that the early Salvationists “sent out ice carts in summer, coal wagons in winter, and salvage crews all year round. They established soup kitchens, rescue homes, employment bureaus, hospitals, shelters, and thrift shops.” Their work was tireless and consequential.

The Salvation Army crowd-gathering techniques were as effective as their innovative social services for the down-and-outers. “In the early days their brass instruments, jingling tambourines, and resonant bass drums clamored over the din of horse-drawn carriages and noisy peddlers,” reports Winston. “Their testimonies, shouted from street corners, captured the curious, while their renditions of popular tunes – ‘Swanee River’ or ‘Tramp, Tramp, Tramp’ rewritten as hymns – roused critics to decry such blasphemous strategems.”

The trailblazing methods – loud music, dancing, posters resembling P. T. Barnum’s advertisements – were not welcomed by respectable religious observers, nor by those outside the fold who were annoyed by their message about a transformed life. The Salvationists were attacked in print and sometimes physically assaulted for their public preaching and worship services. One writer actually had the ugly audacity to group African Americans with “whores” and “bums.” “A more motley, vice-smitten, pestilence-breeding, congregation could seldom be found in a house of worship,” wrote the jaundiced reporter from the New York Herald. “There were Negroes, dancing girls, prostitutes, and station house tramps sandwiched between well-dressed visitors who had sauntered in out of curiosity. The floors were as clean as a deck of a man-of-war, but in a few minutes they were frescoed with tobacco juice, the stench became overpowering, and a yellow-fever pest-house could not have been less attractive.”

Throughout its colorful history, the public mockery and vicious assaults were never able to dim the bright light projected from The Salvation Army. “Whether parading in the streets, singing in the saloons, or appearing on the city’s stages, the Army used the venues and forms of the contemporary culture to promote an alternate, even subversive message,” writes Winston. Booth never wanted to surrender one square inch of life or culture to his spiritual enemy. “Why should the devil have all the dancing?” he asked. “You must sing good tunes … I don’t care much whether you call it secular or sacred. I rather enjoy robbing the devil of his choicest tunes, and, after his subjects themselves, music is about the best commodity he possesses,” he concluded. “It is like taking the enemy’s guns and turning them against him.”

It’s a provocative countercultural message – similar to the Red Kettle in front of a department store at Christmas time. Yes, enjoy Christmas, Booth might say, but please don’t forget the less fortunate. The kettle was first utilized in San Francisco in 1891 when Joseph McFee wanted to raise funds for a free Christmas dinner for the poor. He borrowed a large crab pot and hung it from a tripod on a busy street. With a sign that read, “Fill the Pot for the Poor – Free Dinner on Christmas Day,” he was able to collect enough spare change to feed more than 1,000 hungry men, women, and children.

That’s the creative spirit and spiritual legacy of The Salvation Army. It has earned our support.