While sifting through obscure Spanish colonial records, it was discovered a few years ago that the very first St. Patrick’s Day parade was not conducted in Boston, Chicago, nor New York City.

Instead, the Irish feast day was celebrated in modern day St. Augustine, Florida, in 1601.

“They processed through the streets of St. Augustine, and the cannon fired from the fort,” said Prof. J. Michael Francis of the University of South Florida at St. Petersburg, who discovered the document. The ancient records named “San Patricio” as “the protector” of the area’s maize fields. “So here you have this Irish saint who becomes the patron protector of a New World crop, corn, in a Spanish garrison settlement,” he said.

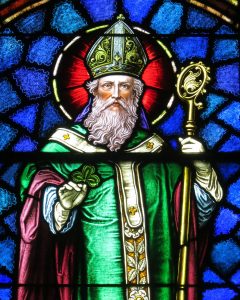

This strange twist in the story and celebration of St. Patrick, a fifth century holy man, is really not that surprising. Historians are constantly attempting to set the record straight. After all, Patrick was not Irish (born in Britain of a Romanized family). He was never canonized as a saint by the Catholic Church. Interestingly, there are two St. Patrick’s Cathedrals in Armagh, Ireland – one Catholic and one Protestant. Remarkably, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin is both Catholic and Protestant.

The legacy of Ireland’s patron saint blurs a lot of lines – but, he is notably worth celebrating.

Patrick was brutally abducted at the age of 16 by pirates and sold as a slave in Ireland. For six agonizing years in a foreign land, he largely lived in abject solitude attending animals. The Christian faith of his family that he found unappealing as a teenager became his spiritual lifeline to sanity and survival while in captivity.

“Tending flocks was my daily work, and I would pray constantly during the daylight hours,” he writes in his Confession – one of only two brief documents authentically from Patrick’s own hand. “The love of God and the fear of him surrounded me more and more – and faith grew and the Spirit was roused, so that in one day I would say as many as a hundred prayers and after dark nearly as many again even while I remained in the woods or on the mountain. I would wake and pray before daybreak – through snow, frost, rain – nor was there any sluggishness in me (such as I experience nowadays) because then the Spirit within me was ardent.”

Through a divine dream, Patrick was inspired to make his escape. His journey as a fugitive was, according to his testimony, a 200 mile trek to the coast. Further miraculous circumstances allowed him to wrangle himself aboard a ship to escape his imprisonment in Ireland. He finally made it back to the loving embrace of his family.

Years later, however, another mystical dream launched his trajectory into the ministry and, ultimately, back to Ireland. “We appeal to you, holy servant boy,” said the voice in the dream, “to come and walk among us.”

For many years, he trained to become a priest. Eventually, in 432 A.D., Patrick returned to the shores of the land where he once was held captive.

“Believe me, I didn’t go to Ireland willingly that first time [when he was taken as a slave] – I almost died there,” he wrote in his Confession. “But it turned out to be good for me in the end, because God used the time to shape and mold me into something better. He made me into what I am now – someone very different from what I once was, someone who can care for others and work to help them. Before I was a slave, I didn’t even care about myself.”

Noted classics scholar Philip Freeman, author of St Patrick of Ireland, points out the distinguished uniqueness of Patrick’s public vulnerability – a trait that was not characteristic of a man of his stature and notoriety. As an elderly and well-known bishop, Patrick begins his Confession with these words: “I am Patrick – a sinner – the most unsophisticated and unworthy among all the faithful of God. Indeed, to many, I am the most despised.”

“The two letters are in fact the earliest surviving documents written in Ireland and provide us with glimpses of a world full of petty kings, pagan gods, quarreling bishops, brutal slavery, beautiful virgins, and ever-threatening violence,” writes Freeman. “But more than anything else, they allow us to look inside the mind and soul of a remarkable man living in a world that was both falling apart and at the dawn of a new age. There are simply no other documents from ancient times that give us such a clear and heartfelt view of a person’s thoughts and feelings. These are, above all else, letters of hope in a trying and uncertain time.”

While there are many beautiful, miraculous, and fantastical stories about St. Patrick, his Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus – the other document authentically written by Patrick – exposes his heart and soul. It portrays the character of a man worthy of emulation and celebration. His humility, empathy, and righteous indignation scorches the letter as he takes up the cause of the voiceless captives and powerless victims of slavery – a common practice in the fifth century.

The fiery correspondence addresses the horrific news that a group of newly baptized converts were killed or taken into slavery on their way home by a petty British king named Coroticus, known to be at least nominally a Christian.

“Blood, blood, blood! Your hands drip with the blood of the innocent Christians you have murdered – the very Christians I nourished and brought to God,” Patrick writes. “My newly baptized converts, still in their white robes, the sweet smell of the anointing oil still on their foreheads – you murdered them, cut them down with your swords!”

Violating cultural and ecclesiastical protocols, the letter was sent broadly and caused a stir. Courageously, Patrick launched a public ruckus – outside his governance – over the “hideous, unspeakable crimes” because he believed that God truly loved the Irish – even if church leaders elsewhere did not. Patrick’s vision for the love of God was expansively generous. “I am a stranger and an exile living among barbarians and pagans, because God cares for them,” he writes (emphasis added).

“Was it my idea to feel God’s love for the Irish and to work for their good?” Patrick writes. “These people enslaved me and devastated my father’s household! I am of noble birth – the son of a Roman decurion – but I sold my nobility. I’m not ashamed of it and I don’t regret it because I did it to help others. Now I am a slave of Christ to a foreign people – but this time for the unspeakable glory of eternal life in Christ Jesus our master.”

Having been captive, he does not write about slavery whimsically. He was an outspoken voice opposing slavery at a time when it was simply considered commonplace. Furthermore, he was a fierce advocate for those who were most vulnerable and abused in captivity.

“But it is the women kept in slavery who suffer the most – and who keep their spirits up despite the menacing and terrorizing they must endure,” he writes in his Confession. “The Lord gives grace to his many handmaids; and though they are forbidden to do so, they follow him with backbone.”

When Patrick heard about the bloody attack and abductions after the baptism service, he sought to reason with Coroticus: “The very next day I sent a message to you with a priest l had taught from childhood and some other clergy asking that you return the surviving captives with at least some of their goods – but you only laughed.”

In response, Patrick derides Coroticus and his men as “dogs and sorcerers and murderers, and liars and false swearers … who distribute baptized girls for a price, and that for the sake of a miserable temporal kingdom which truly passes away in a moment like a cloud or smoke that is scattered by the wind.”

In order to make his point, he prays: “God, I know these horrible actions break your heart – even those dwelling in Hell would blush in shame.”

With pastoral care, Patrick addresses the memory of those killed after their baptism: “And those of my children who were murdered – I weep for you, I weep for you … I can see you now starting on your journey to that place where there is no more sorrow or death. … You will rule with the apostles, prophets, and martyrs in an eternal kingdom.”

Even in an inferno of justifiable rage, Patrick extends an olive branch of redemption: “Perhaps then, even though late, they will repent of all the evil they have done – these murderers of God’s family – and free the Christians they have enslaved. Perhaps then they will deserve to be redeemed and live with God now and forever.”

“The greatness of Patrick is beyond dispute: the first human being in the history of the world to speak out unequivocally against slavery,” writes historian Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization. “Nor will any voice as strong as his be heard again till the seventeenth century.”

All around the globe, March 17 is set aside to honor a great man who overcame fear with faith, overcame hate with love, and overcame prejudice with hope. Although he had every reason in the world to resist the dream to return to “walk among” the Irish, Patrick responded to the God-given impulse of his heart – even when it was most difficult. He knew the dangers and challenges and returned anyway.

Patrick offered himself as a living example of what new life could look like for the Irish. “It is possible to be brave – to expect ‘every day … to be murdered, betrayed, enslaved – whatever may come my way’ – and yet be a man of peace and at peace, a man without sword or desire to harm, a man in whom the sharp fear of death has been smoothed away,” writes Cahill of Patrick. “He was ‘not afraid of any of these things, because of the promises of heaven; for I have put myself in the hands of God Almighty.’ Patrick’s peace was no sham: it issued from his person like a fragrance.”

Happy St. Patrick’s Day.